|

|

Conspirators, Killers, and Victims |

Genocide in Rwanda

|

Who Were the Conspirators?

By 'conspirators', we mean here the people who actually carried out the organization of murder squads, distributed weapons and gave or relayed instructions at a high level. We do not mean those who gave the genocide intellectual inspiration such as Ferdinand Nahimana or Casimir Bizimungu, great as their responsibility may be. We do not mean either the gun-and machete-toting actual killers.

As in any genocide, the question of who actually gave the orders is not an easy one to answer. Even in the well-researched case of the German genocide of the Jews, although everyone knows by now relatively well how it was carried out, the precise decision-making mechanism which set the process in motion remains shrouded in uncertainties. But in the case of Rwanda, after a number of political actors have spoken of their roles, doubts are relatively limited and they concern more the 'how' than the 'who.' The same names crop up again and again, whether in the reports of human rights groups or in the testimony of independent observers of various political persuasions.

It seems that, inasmuch as there was a general organizer of the whole operation, this distinction has to go to Colonel Theoneste Begosora, director of services in the Ministry of Defense and behind-the-scenes creator of the 'Provisional Government.' It seems to have been he who coordinated the 'final solution' activities as long as they retained enough coherence to be coordinated. Next in the line of responsibility is the Defense Minister, Major-General Augustin Bizimana, who oversaw the logistics and also influenced the reluctant elements in the FAR so that they would not stand in the way. His military aides were mostly colonel Aloys Ntabakuze, commander of the paratroopers, and Lieut.-Colonel Protais Mpiranya, head of the Presidential Guard (GP). Other military men who seem to have played an essential role in articulating army resources and militia action are Lieut.-Colonel Leonard Nkundiye, the former GP commander, Captain Pascal Simbikangwa who supervised militia killings in Kigali, and his second-in-command Captain Gaspard Hategekimana. All these people acted at the national level. Locally one can mention Gendarmerie Colonel Nsengiyumva who directed the slaughter in Gisenyi and Colonel Muvunyi who did the same in Butare. Many civilians were also directly involved such as Joseph Nzirirera, the secretary-general of MRND (D), who coordinated the Interhamwe operations; Pascal Musabe, a bank director who was one of the militia organisers at the national level; the businessman Felicien Kabuga who financed the RTLMC and the Interhamwe; and Robert Kajuka, leader of the CDR militia, the Impuzamugambi, although he himself was a Tutsi. In the interior, the local organisers of the massacres were almost invariably the prefets, with particular distinction for viciousness going to Emmanuel Bagambiki, prefet of Cyangugu and Clement Kayishema, prefet of Kibuye. In some case the main organiser could be a militant outsider, as with Remy Gatete, formerly a simple bourgmestre of Murambi commune in Byumba, who had moved to Kibungo prefecture by the time of the genocide and who organised the massacres in the east before fleeing to Tanzania and becoming a 'refugee leader' at Benaco camp.

These people seemed to think according to a pattern familiar to those who have studied the work of various 'negationist' historians of the Nazi genocide. Verbally attack the victims, deny-even in the face of the clearest evidence-that any physical violence is taking place or has taken place and fudge the responsibility issue so that, although there are victims, the killers' identities remain vague and undefined, almost merging into non-existence. When talking to your supporters never claim any 'credit' for what you are actually doing but hint at the great benefits derived from the nameless thing which has been done, sharing complicity in the unspoken secret with your audience.

So we can see that the actual organisers of the genocide were a small tight group, belonging to the regime's political, military and economic elite who had decided through a mixture of ideological and material motivation radically to resist political change which they perceived as threatening. Many of them had collaborated with the 'Zero Network' killer squad in earlier smaller massacres, and shared a common ideology of radical Hutu domination over Rwanda. They did not belong exclusively to the inner circle of akazu if by this expression one means the people closest to President Habyarimana. Rather it seems that the leaders in the conspiracy were the people who had once been close to the President but who had somewhat parted company with him. On the whole, they seem to have been closer to the 'other side' of the akazu, that is Mme Habyarimana and 'le clan des beaux-freres.' Their efficiency in carrying out the killings proves that these had been planned well in advance. But the particular chilling quality of that efficiency is that, as in other genocides, it would not have been enough had it not been for two other factors: the capacity to recruit fairly large numbers of people as actual killers and the moral support and approbation of a large segment--possibly a majority of the population.

Who Were the Killers?

There are some differences between the situations in the capital and in the interior prefectures. In Kigali things developed rapidly. They were also highly centralised. The executions were begun by the Presidential Guards as early as the evening of the 6th. They started killing during the night and they managed to dispose of most of the 'priority targets'--the politicians, journalists, and civil rights activists--within less than thirty-six hours. The GP had a strength of about 1,500--enough to terrorise the capital within a short time. But they immediately called for help from the Interhamwe and Impuzamugambi militias, which had been waiting for such a moment from the date of their conception.

These militias tended--usually though not always--to be recruited from low-class people. The camaraderie, the numerous material advantages and even a form of political ideal made them attractive to some middle-class young people. Country-wide, their numbers were estimated at about 50,000, that is approximately the strength of the regular armed forces. Their equipment was simple, some AK-47 assault rifles, a lot of grenades and the all-purpose slashing knives or machetes called 'panga' in Swahili. Many of them had received a military training, often thanks to the French army as we have seen. In Kigali, they manned the roadblocks and took part in the house-to-house searches. They also acted as the executioners. It could be that in a given neighbourhood, some local people would work 'part-time' as Interahamwe, either for the sake of looting the victims' houses or, on the contrary, to be seen as 'one of the boys' and be able to protect their own house against looters. On the whole, their discipline was poor, especially among new members recruited in the heart of the action. Since these new members tended to be street boys who were drunk most of the time, the militias crumbled into armed banditry in the later course of the war as the administrative structure which had recruited and supported them fell apart.

Till this late stage though, the killers were controlled and directed in their task by the civil servants in the central government, prefets, bourgmestres and local councillors, both in the capital and in the interior. It was they who received the orders from Kigali, mobilised the local Gendarmerie and Interahamwe, ordered the peasants to join in the man-hunts and called for FAR support if the victims put up too much resistance. There was only one case of non-compliance with the killing orders. It came from Jean-Baptiste Habyarimana (no relation to the late President), the only Tutsi prefet in the country who was at the head of the Butare prefecture. Nothing happened in Butare for two weeks till, angered by his 'inaction', Interim Government President Sindikubwabo (one of the rare Butare men in the government) came down and gave an inflammatory speech, asking the people if they were 'sleeping' and urging them to violent deeds. On the 20th the prefet was replaced by the extremist Sylvain Ndikumana, GP elements were flown down from Kigali by helicopter, and the killing started immediately.

The efficiency of the massacres bore witness to the quality of Rwandese local administration and also to its responsibility. If the local administration had not carried out orders from the capital so blindly, many lives would have been saved. This fact will of course cause immense problems for any future government which has to run a country where almost the entire local civil service should be charged with crimes against humanity. In the horror at the behaviour of an administration cold-bloodedly prepared to massacre its own population, there is a mitigating circumstance the mention of which is hardly reassuring. All these administrators were not only civil servants, but also MRND (D) members and as such doubly responsible to the state. As we saw in Chapter 1, there had always been a strong tradition of unquestioning obedience to authority in the pre-colonial kingdom of Rwanda . This tradition was of course reinforced by both the German and Belgian colonial administrations. And since independence the country had lived under a well-organised tightly-controlled state. When the highest authorities in that state told you to do something you did it, even if it included killing. There is some similarity here to the Prussian tradition of the German state and its ultimate perversion into the disciplined obedience to Nazi orders.

Political scientists tell us that the state can be defined by its monopoly of legitimate organised violence. Where does the legality of the exercise of that monopoly stop? In time of war, people who refuse to carry out orders to commit violent acts can be shot. And we will see that violence and compulsion were used in the Rwandese case. This obviously constitutes no excuse, especially since, as we will also see, some people found in their religious faith or simply in their individual conscience the strength to resist the orders. But we have to realise that this is a society where two factors combine to make orders hard to resist. The first is a strong state authoritarian tradition going back to the roots of Rwandese culture. The Tutsi abami were definitely not constitutional monarchs, and killing was even an accepted sign of their political health--the difference being of course in the order of magnitude and social inscription of the killings. The second is an equally strong acceptance of group identification. In Rwanda, as elsewhere, a man is judged by his individual character, but in Rwandese culture he does not stand alone but is part of a family, a lineage and a clan, the dweller on a certain Hill. On top of this age-old feeling, the tight administrative practices (and regional discriminatory policies) of the regime had reinforced this 'collective grounding of identity'. When the authorities gave the orders to kill and most of the group around you complied, with greater or less enthusiasm, it took a brave man indeed to abandon solidarity with the crowd and refuse to go along. And such a heroic position would not be without personal danger. Sadistic killers such as the notorious Murambi bourgmestre Remy Gatete seem to have been in a small minority and heroes such as prefet Jean-Baptiste Habyarimana were even rarer. The vast majority of civil servants carried out their murderous duties with attitudes varying from careerist eagerness to sullen obediences.

The Tutsi and opposition Hutu were duly listed, their houses were known, and few of those marked out to die had a chance to hide. To carry out their task the administrators relied first on the Gendarmie, this rural police of whose training the French were so proud. The bourgmestre simply called on the next Gendarmerie unit and they fanned out among the ingo, shooting and flushing people out of their houses. But the Gendarmes could not perform such a herculean task as attempting to kill about 10% of the population all by themselves. Inter-service collaboration was needed, and so was the enrollment of 'volunteers.' The FAR did not at first take a leading role in the genocide. But after the failed attempt by Colonel Gatsinzi to keep them out of the unfolding tragedy, they were slowly drawn more and more deeply into the collective slaughter.

Other actors in the genocide were the Hutu Barundi refugees who had fled Burundi after the murder of President Melchior Ndadaye in October 1993 and the inter-communal massacres following that event. The MRND (D) had started recruiting them into the Interahamwe soon after their arrival in Rwanda and the UNHCR felt obliged to complain (without effect) to the Rwandese authorities. After 6 April many of them took an active part in the killing.

Nevertheless, the main agents of the genocide were the ordinary peasant themselves. This is a terrible statement to make, but it is unfortunately borne out by the majority of the survivors' stories. The degree of compulsion exercised on them varied greatly from place to place but in some areas, the government version of a spontaneous movement of the population to 'kill the enemy Tutsi' is true. This was the result of years of indoctrination in the 'democratic majority' ideology and of demonisation of the 'feudalists.' So even in the cases where people did not move spontaneously but were forced to take part in the killings, they were helped along into violence by the mental and emotional lubricant of ideology. We can see it for example in the testimony of this seventy-four year-old 'killer' captured by the RPF: 'I regret what I did. [...] I am ashamed, but what would you have done if you had been in my place? Either you took part on the massacre or else you were massacred yourself. So I took weapons and I defended the members of my tribe against the Tutsi.

Even as the man pleads compulsion, in the same breath he switches his discourse to adjust it to the dominant ideology. He acknowledges that he killed (under duress) harmless people, and yet he agrees with the propaganda view (which he knows to be false) by mythifying them as aggressive enemies. If the notion of guilt presupposes a clear understanding of what one is doing at the time of the crime, then there were at that time in Rwanda, to use the vivid expression coined by the historian Jean-Pierre Chretien, a lot of 'innocent murderers.' Such 'victim-killers' were often disgusted and horrified at what they were doing which is partly why large groups of Hutu peasants started to flee their Hills even before the arrival of the RPF troops. In Tanzania, the objective of the first stage of this mass exodus, some of the refugees denounced their own bourgmestres who were walking along in the crowd. A Tanzanian police officer, Jumbe Suleiman, who saw them as they were crossing at Rusumo was struck by their reaction: 'When Gatete [Remy Gatete, bourgemestre of Murambi] crossed the bridge over the river which marks the border between Rwanda and Tanzania, people started to shout: "This is Gatete! He is a murderer! Arrest him!" If we had not intervened, he would have been lynched.' In the hysteria of Rwanda in April 1994, almost anybody might turn into a killer. But the responsibility lies with the educated people--with those in positions of authority, however small, who did not have the strength (or maybe even the wish) to question the poisonous effluents carried by their cultural stream.

There was of course also an element of material interest in the killings, even in the countryside. The killers looted household belongings and slaughtered the cattle Meat became very cheap and grand feasts were held, as if in celebration of the massacre. villagers also probably had a vague hope that if things settled down after the massacres they could obtain pieces of land belonging to the victims, a strong lure in such a land-starved country as Rwanda. But greed was not the main motivation. It was belief and obedience--belief in a deeply-imbibed ideology which justified in advance what you were about to do, and obedience both to the political authority of the state and to the social authority of the group. Mass-killers tend to be men of the herd, and Rwanda was no exception.

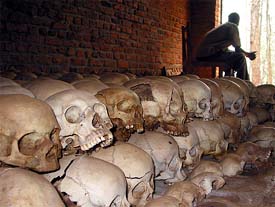

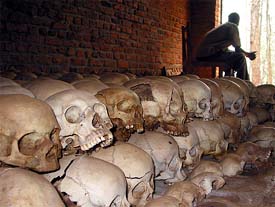

Who Were the Victims?

The vast majority of victims were people belonging to the Tutsi social group. All of them were slated to die. The killers did not spare women, old people, children or even babies. The 'bush clearing', to use the Interahamwe euphemism, was absolutely thorough. In the countryside, where people knew each other well, identifying the Tutsi was easy and they had absolutely no chance of escaping. Since Hutu and Tutsi are not tribes but social groups within the same culture, there was no separate dwelling pattern. They lived side by side in similar huts, and given the demographic ratio, each Tutsi household was usually surrounded by several Hutu families, making concealment almost impossible. In the countryside, in contrast to the city, there was no noticeable difference of economic level between Tutsi and Hutu. The 'small Tutsi' from the Hills were in no way different from their Hutu neighbours, except perhaps in their physical appearance. but it did not matter because the Tutsi or Hutu identities of the villagers were public knowledge.

It was not the same thing in the towns and even more in Kigali where people did not know each other. There the Interahamwe manning the roadblocks asked people for their identity cards. To be identified on one's card as a Tutsi or to pretend to have lost one's papers meant certain death. Yet to have a Hutu ethnic card was not automatically a ticket to safety. In Ruhengeri or Gisenyi and at times in Kigali, southern Hutu suspected of supporting the opposition parties were also killed. And people were often accused of having a false card, especially if they were tall and with a straight nose and thin lips. Frequent intermarriage had produced many Hutu-looking Tutsi and Tutsi-looking Hutu. In towns or along the highways, Hut who looked like Tutsi were very often killed, their denials and proffered cards with the 'right' ethnic mention being seen as a typical Tutsi deception.

Of course, Hutu militants or sympathisers of the opposition parties were also killed, a fact which gives this genocide its peculiar mixed character both racially and politically. And as in many such situations, intellectuals were also a target: journalists, professionals and university people were highly suspect because they thought too much and as such were probably not good citizens, even when they were Hutu. In Butare, almost everybody who lived on campus, both students and teachers, the vast majority of them Hutu, were massacred after 21 April. So too were almost all the doctors at the hospital.

Although it seems that few people were killed purely for robbery, there was nevertheless a strong element of social envy in the killings, and in the rural areas this could work at a very simple level. In the vivid words of a survivor, 'The people whose children had to walk barefoot to school killed the people who could buy shoes for theirs.'

From THE RWANDA CRISIS by Gerard Prunier

Reprinted with permission of the author, C. Hurst & Co.Publishers, London and Columbia University Press.

Copyright 1995. All rights reserved.

[Federal law provides severe civil and criminal penalties for the unauthorized reproduction, distribution, or exhibition of copyrighted materials.]

| Hotel Rwanda | Rwanda Chronology |