|

I.

Review market structure characteristics from beginning of

Chapter 7.

II.

Monopolistic Competition: Characteristics, Occurrence, Price

and Output Determination

A.

Monopolistic competition refers to a market situation in which a

relatively large number of sellers offer similar but not identical

products.

1.

Each firm has a small percentage of the total market.

2.

Collusion is nearly impossible with so many firms.

3.

Firms act independently; the actions of one firm are ignored

by the other firms in the industry.

B.

Product differentiation and other types of nonprice

competition give the individual firm some degree of monopoly power

that the purely competitive firm does not possess.

1.

Product differentiation may be physical (qualitative).

2.

Services and conditions accompanying the sale of the product

are important aspects of product differentiation.

3.

Location is another type of differentiation.

4.

Brand names and packaging lead to perceived differences.

5.

Product differentiation allows producers to have some control

over the prices of their products.

C.

Similar to pure competition, under monopolistic competition

firms can enter and exit these industries relatively easily.

D.

Examples of real‑world industries that fit this model include

grocery stores, restaurants, medical care, and real estate sales.

E.

Monopolistic Competition:

Price and Output Determination

1. The

firm’s demand curve is highly, but not perfectly, elastic.

It is more elastic than the

monopoly’s demand curve because the seller has many rivals

producing close substitutes.

It

is less elastic than in pure competition, because the seller’s

product is differentiated

from its rivals, so the firm has some control over price.

2. In the

short‑run situation, the firm will maximize profits or minimize

losses by producing

where marginal cost and marginal revenue are equal, as was

true in pure competition and

monopoly. The

profit‑maximizing situation is illustrated in Figure 9.1a, and the

loss‑minimizing

situation is illustrated in Figure 9.1b.

3. In the

long‑run situation, the firm will tend to earn a normal profit only,

that is, it will

break even (Figure 9.1c).

a. Firms

can enter the industry easily and will if the existing firms are

making an

economic profit. As

firms enter the industry, this decreases the demand curve facing

an individual firm as

buyers shift some demand to new firms; the demand curve will

shift until

the firm just breaks even.

If the demand shifts below the break‑even point

(including a normal profit), some firms will leave the industry in

the long run.

b. If firms

were making a loss in the short run, some firms will leave the

industry. This

will

raise the demand curve facing each remaining firm as there are fewer

substitutes for buyers.

As this happens, each firm will see its losses disappear

until it reaches

the break‑even (normal profit) level of output and price.

c.

Complicating factors are involved with this analysis.

i.

Some firms may achieve a measure of differentiation that is not

easily duplicated

by rivals (brand names, location, etc.) and can realize

economic profits even in

the long run.

ii. There

is some restriction to entry, such as financial barriers that exist

for new

small businesses, so economic profits may persist for

existing firms.

iii. Long‑run

below‑normal profits may persist, because producers like to maintain

their way of life as entrepreneurs despite the low economic

returns.

III.

Monopolistic Competition and Economic Efficiency

A.

Review the definitions of allocative and productive efficiency:

1.

Allocative efficiency occurs when price = marginal cost,

i.e., where the right amount of resources are allocated to the

product.

2.

Productive efficiency occurs when price = minimum average

total cost, i.e., where production occurs using the least-cost

combination of resources.

B.

Excess capacity will tend to be a feature of monopolistically

competitive firms (Figure 9.2).

1.

Price exceeds marginal cost in the long run, suggesting that

society values additional units that are not being produced.

2.

Firms do not produce the lowest average-total-cost level of

output (Figure 9.2).

3.

Average costs may also be higher than under pure competition,

due to advertising and other costs involved in differentiation.

C.

Monopolistic Competition:

Product Variety

1. A

monopolistically competitive producer may be able to postpone the

long-run outcome

of just normal profits through product development and

improvement and advertising.

2. Compared

with pure competition, this suggests possible advantages to the

consumer.

a.

Developing or improving a product can provide the consumer with a

diversity of

choices.

b. Product

differentiation is at the heart of the tradeoff between consumer

choice and

productive efficiency.

The greater number of choices the consumer has, the greater

the excess capacity problem.

IV.

Oligopoly:

Characteristics and Occurrence

A.

Oligopoly exists where a few large firms producing a homogeneous or

differentiated product dominate a market.

1.

“A few large producers” is intentionally vague.

If there are dominant firms that can be clearly identified,

and few enough that firms are mutually interdependent in their

pricing and output decisions, then you’ve got oligopoly.

2.

Some oligopolistic industries produce standardized products

(steel, zinc, copper, cement), whereas others produce differentiated

products (automobiles, detergents, greeting cards).

3.

Oligopolies exert some control over price, but mutual

interdependence requires strategic behavior – self-interested

behavior that accounts for the reactions of others.

4.

Illustrating the

Idea: Creative Strategic Behavior

Strategic behavior can come in the form of pricing decisions,

product differentiation, or through creative marketing (creating

perceived product differences).

It can apply to either competitive or collusive behavior

(including cheating on collusive agreements).

B.

Barriers to entry

1.

Economies of scale may exist due to technology and market

share.

2.

The capital investment requirement may be very large.

3.

Other barriers to entry may exist, such as patents, control

of raw materials, preemptive and retaliatory pricing, substantial

advertising budgets, and traditional brand loyalty.

C.

Although some firms have become dominant as a result of

internal growth, others have gained this dominance through mergers.

(Section 7 of the Clayton Act prohibits mergers that “substantially”

lessen competition.

V.

Oligopoly Behavior:

A Game Theory Overview

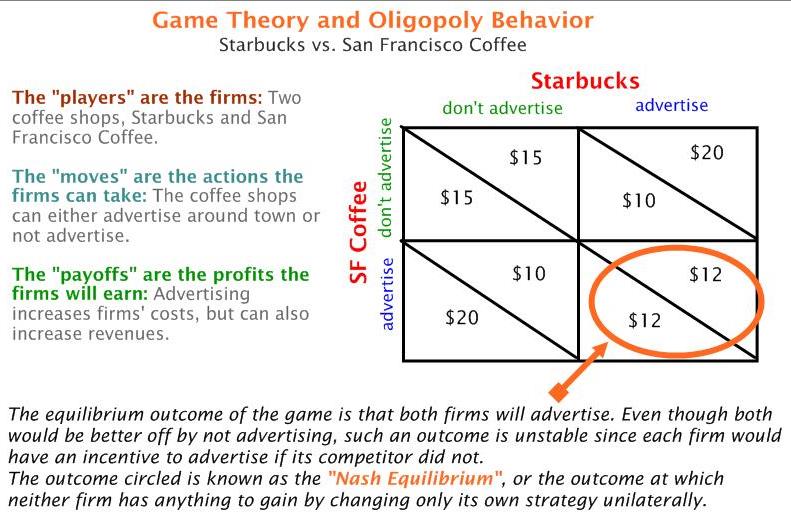

A.

Oligopoly behavior is similar to a game of strategy, such as poker,

chess, or bridge. Each

player’s action is interdependent with other players’ actions.

Game theory can be applied to analyze oligopoly behavior.

A two-firm model or duopoly will be used.

B.

Figure 9.3 illustrates the profit payoffs for firms in a

duopoly in an imaginary athletic-shoe industry.

Pricing strategies are classified as high-priced or

low-priced, and the profits in each case will depend on the rival’s

pricing strategy.

C.

Mutual interdependence is demonstrated by the following:

RareAir’s best strategy is to have a low-price strategy if

Uptown follows a high-price strategy.

However, Uptown will not remain there, because it is better

for Uptown to follow a low-price strategy when RareAir has a

low-price strategy.

Each possibility points to the interdependence of the two firms.

This is a major characteristic of oligopoly.

D.

Another conclusion is that oligopoly can lead to collusive behavior.

In the athletic-shoe example, both firms could improve their

positions if they agreed to both adopt a high-price strategy.

However, such an agreement is collusion and is a violation of

U.S.

anti-trust laws.

E.

If collusion does exist, formally or informally, there is

much incentive on the part of both parties to cheat and secretly

break the agreement.

For example, if RareAir can get Uptown to agree to a high-price

strategy, then RareAir can sneak in a low-price strategy and

increase its profit

VI.

Three oligopoly models are used to explain oligopolistic

price-output behavior.

(There is no single model that can portray this market structure due

to the wide diversity of oligopolistic situations and mutual

interdependence that makes predictions about pricing and output

quantity precarious.)

A.

The kinked-demand model assumes a noncollusive oligopoly.

(Figure 9.4)

1.

The individual firms believe that rivals will match any price

cuts. Therefore, each

firm views its demand as inelastic for price cuts, which means they

will not want to lower prices since total revenue falls when demand

is inelastic and prices are lowered.

2.

With regard to raising prices, there is no reason to believe

that rivals will follow suit because they may increase their market

shares by not raising prices.

Thus, without any prior knowledge of rivals’ plans, a firm

will expect that demand will be elastic when it increases price.

From the total-revenue test, we know that raising prices when

demand is elastic will decrease revenue.

Therefore, the noncolluding firm will not want to raise

prices.

3.

This analysis is one explanation of the fact that prices tend

to be inflexible in oligopolistic industries.

B.

Price leadership is a type of gentleman’s agreement that

allows oligopolists to coordinate their prices legally; no formal

agreements or clandestine meetings are involved.

The practice has evolved whereby one firm, usually the

largest, changes the price first and, then, the other firms follow.

1.

Several price leadership tactics are practiced by the leading

firm.

a.

Prices are changed only when cost and demand conditions have

been altered significantly and industry-wide.

b.

Impending price adjustments are often communicated through

publications, speeches, and so forth.

Publicizing the “need to raise prices” elicits a consensus

among rivals.

c.

Leaders try to avoid price wars that reduce profits.

However, leaders may sometimes reduce price below the

short-run profit-maximizing level to discourage new entrants.

2.

Applying the

Analysis: Challenges to

Price Leadership

a. Price

leadership in oligopoly occasionally breaks down and sometimes

results in a

price war. A

recent example occurred in the breakfast cereal industry in which

Kellogg had been the traditional price leader, but General Mills and

Post were attempting to gain market share.

b. In 2002,

Burger King and McDonald’s engaged in a price war between the

Whoppers and Big “N” Tasty burger.

c. Price

wars eventually end when firms realize that they can increase

profits by

reverting to price leadership.

C.

Cartels and collusion agreements constitute another oligopoly

model. (Figure 9.5)

1.

Game theory suggests that collusion is beneficial to the

participating firms.

2.

Collusion reduces uncertainty, increases profits, and may

prohibit the entry of new rivals.

3.

A cartel may reduce the chance of a price war breaking out

particularly during a general business recession.

4.

The kinked-demand curve’s tendency toward rigid prices may

adversely affect profits if general inflationary pressures increase

costs.

5.

To maximize profits jointly, the firms collude and agree to a

certain price. Assuming

the firms have identical cost, demand, and marginal-revenue date the

result of collusion is as if the firms made up a single monopoly

firm.

6.

Applying the

Analysis: Cartels and Collusion

a. A cartel

is a group of producers that creates a formal written agreement

specifying

how much each member will produce and charge.

The Organization of Petroleum

Exporting Countries (OPEC) is the most significant

international cartel.

b. Cartels

are illegal in the U.S., thus any

collusion that exists is covert and secret.

Examples of these illegal, covert agreements include the 1993

collusion between

dairy companies convicted of rigging bids for milk products

sold to schools and, in 1996, American agribusiness Archer Daniels

Midland, three Japanese firms, and a

South Korean firm were found to have conspired to fix the

worldwide price and sales

volume of a livestock feed additive.

7.

There are many obstacles to collusion:

a.

Differing demand and cost conditions among firms in the

industry;

b.

A large number of firms in the industry;

c.

The incentive to cheat;

d.

Recession and declining demand (increasing ATC);

e.

The attraction of potential entry of new firms if prices are

too high; and

VII.

Oligopoly and Advertising

A.

Product development and advertising campaigns are more difficult to

combat and match than lower prices.

B.

Oligopolists have substantial financial resources with which

to support advertising and product development.

C.

Table 9.1 lists the 10 leading

U.S.

advertisers in 2003.

D.

Advertising can affect prices, competition, and efficiency both

positively and negatively.

1.

Advertising reduces a buyers’ search time and minimizes these

costs.

2.

By providing information about competing goods, advertising

diminishes monopoly power, resulting in greater economic efficiency.

3.

By facilitating the introduction of new products, advertising

speeds up technological progress.

4.

If advertising is successful in boosting demand, increased

output may reduce long run average total cost, enabling firms to

enjoy economies of scale.

5.

Not all effects of advertising are positive.

a.

Much advertising is designed to manipulate rather than inform

buyers.

b.

When advertising either leads to increased monopoly power, or

is self-canceling, economic inefficiency results.

6.

Global Snapshot: The World’s

Top 10 Brand Names

VIII.

Oligopoly and Efficiency

A.

Allocative and productive efficiency are not realized because price

will exceed marginal cost and, therefore, output will be less than

minimum average-cost output level (Figure 9.5).

Informal collusion among

oligopolists may lead to

price and output decisions that are similar to that of a pure

monopolist while appearing to involve some competition.

B.

The economic inefficiency may be lessened because:

1.

Foreign competition has made many oligopolistic industries

much more competitive when viewed on a global scale.

2.

Oligopolistic firms may keep prices lower in the short run to

deter entry of new firms.

3.

Over time, oligopolistic industries may foster more rapid

product development and greater improvement of production techniques

than would be possible if they were purely competitive.

|