|

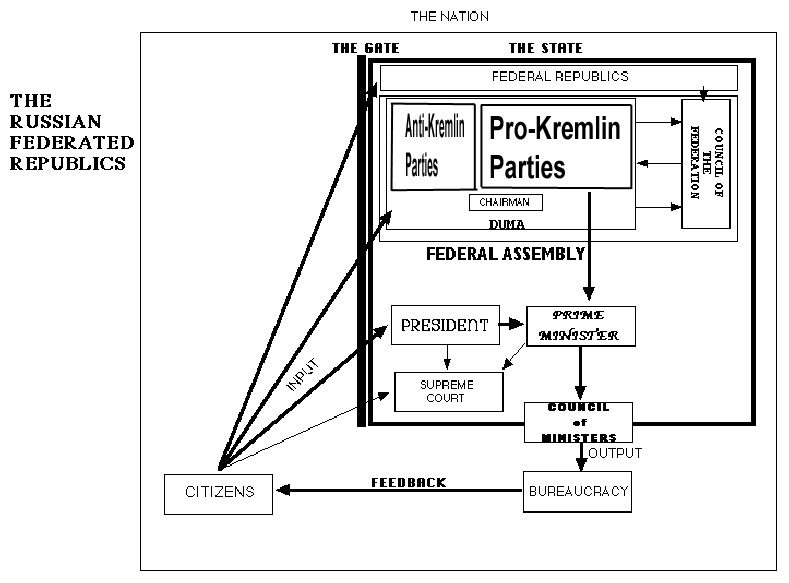

Political

Structure

Initially

one of the deputies to the Upper House was the regional governor,

while the other was selected by the regional legislature. However, in 2000 the

law was changed to make both deputies appointed by the regional governor, and when

regional governors became appointed by the president in 2004, the President of

the Federation essentially

gained the power to select representatives to the upper house.

Foreign affairs:

Sergei Lavrov

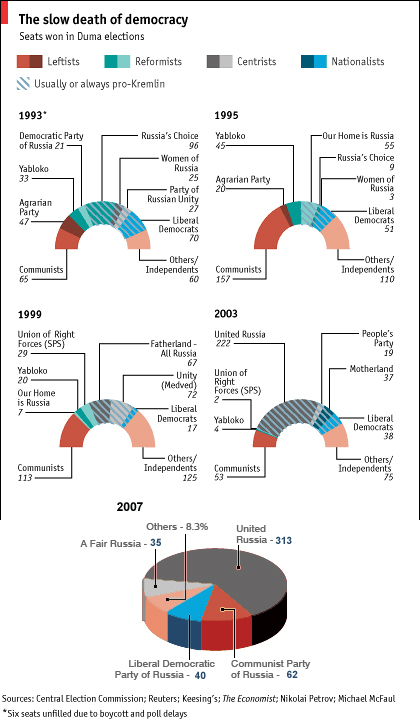

Russia's hollow political scene is dominated by Vladimir Putin. Putin was elected president in March 2000, easily re-elected in 2004, and--constrained by a two term limit on consecutive presidential terms--had his chosen successor, Dmitri Medvedev, elected in 2008; only to have Medvedev immediately appoint Putin Prime Minister. Russia's fading democracy has suffered as a result of his authoritarian tactics. Regional elections in March 2007 marked the start of a political season that continued with December's Duma elections, which Putin's party, United Russia, won overwhelmingly, amidst accusations of fraud and browbeating. But even were they not beaten and suppressed, the president's critics would not command much support from an apathetic public. The vast majority of the population supports Putin. His rule has coincided with a spectacular rise in oil prices and improved living standards. Political clans are entrenched in the Kremlin A number of political clans, rather than political parties, act as distinct and independent political forces in Russia. After the president, Vladimir Putin, removed the last high-profile members of the Yeltsin-era "Family" from power, the siloviki became by far the most prominent political class. According to a study published in 2003, the siloviki—members of the security services, the military and the police—at the time occupied almost 60% of all power positions in Russia, compared with less than 5% during Mikhail Gorbachev's rule. Although the siloviki do not constitute a coherent group, they share a belief in the need for a strong state and a distaste for the wealth and influence acquired by Russia's business oligarchs. The largest group of the siloviki are hard-liners led by Sergei Ivanov. The Hard-liners have set the pace on prosecution of the oligarchs, and the consolidation and nationalization of industry. They have publicly stated their belief in Russia's rightful place among the great world powers, and their regret for the fall of the Soviet Union, and have led the revision of history and education to show the Soviet system in a more positive light. Another, smaller political group comprises the so-called St Petersburg liberals, led by Kudrin and Gref, emphasize more free market liberalization. Kremlin-watchers have tried to infer Mr Putin's political plans from the shifting balance of power between all these political groups. However, the appointment of Premiers and other high-level officials that do not belong to either group indicates that Putin's main objective is to balance these groups' competing influence, and to stand above them. Parties tend to be weak and poorly institutionalized The party political scene in Russia was highly volatile and fragmented throughout the 1990s but has settled considerably since then. Rather than consolidating into a Western-style party political system—with parties offering competing programs to distinct social groups—Russia's parties define themselves mainly by their support or opposition to the Kremlin. Although the 2001 law on political parties requires all registered parties to have a program and local offices, only two of the 23 parties registered for the 2007 Duma election had a distinct ideology, a loyal following and a well-established branch network—namely, the pro-Western Yabloko party and the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF). This continues to be the case. Other parties tend to be loose groupings, which fall into one of two categories: they are either artificial creations to provide the Kremlin with a power base in the Duma (the most prominent current example is United Russia, although a left-wing, pro-Kremlin party—Just Russia—has now also emerged), or they serve as political platforms for ambitious individuals, with little ideological content. Vladimir Zhirinovsky's Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR)—neither liberal nor particularly democratic—is the longest-standing example.

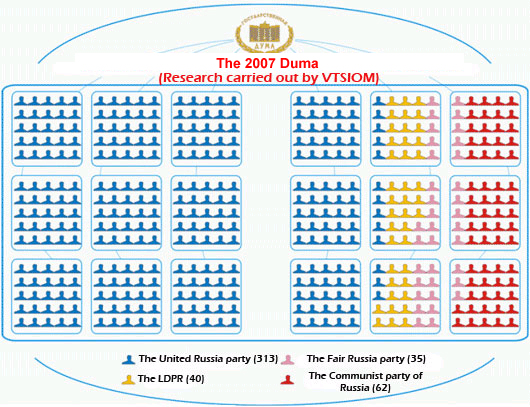

United Russia wins near-complete control of the Duma United Russia—the Duma's strongest political force—was set up in February 2002 by means of a merger of the pro-Kremlin Unity and the Fatherland-All Russia movement (OVR). The two had originally been rivals in the run-up to the 1999 parliamentary election, when the Kremlin helped to set up Unity as a counterweight to the OVR. United Russia's main attraction is its close association with Putin. Although United Russia lacks internal discipline and coherence, the absence of a distinct political program allows it to attract Putin-supporters from vastly different parts of the population. United Russia received a 38% share of the party-list vote in the 2003 Duma election and won 102 single-mandate seats; the party won 66% of the vote and 313 seats in the 2007 election, giving it the 2/3ds control of the Duma necessary to amend the constitution. The Communist Party remains strong and well organized The CPRF, the successor to the ruling party of the Soviet era, was launched in February 1993 and remains one of Russia's largest and best-organized political parties. In October 2006 the CPRF reported having 134,000 members across the country. Although the CPRF has a better-defined program than most other Russian parties, it still comprises an ideologically incoherent coalition of social democrats, Stalinists and nationalists. For many years the CPRF could rely on a loyal support base of around 30% of the electorate. However, in the 2003 Duma election it received a mere 13% of the party-list vote and lost half of its parliamentary mandates. Around 40% of the CPRF's supporters are over the age of 55, and the party's unreconstructed ideas and uncharismatic politicians—in particular, the party leader, Gennady Zyuganov—have little appeal for younger voters or for the emerging middle class. Nevertheless, the party has recently begun to make at least some inroads among younger voters, and once again will function as the largest opposition party--in fact the only oppostion party--in the Duma after the 2007 election. A new leftist party emerges in 2006 A new left-of-center party appeared in 2006 through the merger of Motherland (Rodina), the Pensioners' Party, and the Party of Life. Designed to compete with the CPRF in capturing votes among left-wing voters, the new formation, called Just Russia-- sometimes translated as "Fair" Russia--is headed by Sergei Mironov, speaker of the Federation Council (the upper house of parliament). Although it claims to offer an alternative to United Russia, the new party is similarly loyal to the presidential administration. The party's leaders have denied suspicions that it is a Kremlin creation. However, a left-leaning Just Russia would be useful to displace the CPRF as a more loyal "opposition" party—possibly even as a foundation for the appearance of the two-party system that Putin appears to favor. With a membership of around 340,000, the new party came in fourth in the 2007 Duma election easily passing the new 7% hurdle, and has already secured almost the same number of votes as the CPRF in local elections. The new grouping should see its vote share rise further as its name recognition increases. The LDPR remains the main nationalist group Russia's nationalist groups are fixtures on the political scene and performed well in the 2003 parliamentary election. The LDPR, led by the controversial Vladimir Zhirinovsky, obtained almost as many list votes as the CPRF and is expected to pass the electoral threshold again in the 2007 Duma elections, even though its membership base has fallen by more than half since the mid-1990s. Rodina, now part of the Just Russia party, polled a better than expected 9% in the party-list vote for the Duma in 2003, on the back of the nationalist rhetoric. The large share of votes for the nationalists represents a broader development among the Russian population. Young Russians, in particular, are rediscovering national pride—which often goes alongside anti-Western sentiment and racial hatred of people from the Caucasus and Central Asia. However, neither the LDPR nor the new Just Russia party is an independent political force likely to ride the wave of growing nationalism. Their leaders did not dare to criticize the Kremlin during the 2003 election campaign, and will remain loyal in 2007. Liberal forces: Yabloko and the SPS Russia's main liberal parties are still in disarray after failing to pass the threshold percent of the vote for gaining parliamentary representation in both the 2003 and 2007 Duma elections. The two parties, Yabloko and the Union of Rightist Forces (SPS), could have avoided defeat by pooling their resources ahead of the election. However, such an alliance has long been contentious, reflecting not just the personal animosity of their leaders, but also more profound differences between their constituencies: Yabloko is traditionally the party of the (often impoverished) intelligentsia, whereas SPS voters tend to be young and entrepreneurial. The danger of disappearing from the political scene altogether finally pushed the two parties into a coalition for contesting the December election to the Moscow city Duma, which permitted the two parties to cross the threshold for representation in the Moscow Duma. It is still possible. but unlikely, that the two will put aside their differences permanently and work together in the next Duma election.

|